The mining of ores underground signified a new boldness in human exploration. But,

like the development of glass, iron was a long time arriving to the form

and utility we know today.

The mining of ores underground signified a new boldness in human exploration. But,

like the development of glass, iron was a long time arriving to the form

and utility we know today.

Back before we learned how to extract iron from ore, we relied on meteorites for iron. The meteorite was the leftover husk (mostly an iron/nickel) from a comet or asteroid that got caught up in earth’s atmosphere and hit the ground.They most likely arrived from Mars or another part of the solar system.

The Metallic Meteorite: A literal civilization-starter kit, care of the solar system, via some loser comet.

“Iron from meteors was greatly prized for tool-making,” T.K. Derry and Trevor I. Williams wrote, in "A Short History of Technology." One meteor that fell in Greenland was used Eskimos for more than a century.

Despite this early discovery, it took centuries until we started making use of iron again. It was as if it didn't occur to anyone for a few centuries that, after the iron in the meteorites ran out, there may be more iron buried under the land itself.

Instead, copper was readily adopted, peaking at about 2000 B.C.. Copper's popularity became intertwined with tin, an alloy of the two creating bronze. Who knows how those two got together, maybe an accidental melding in the smelting process of the two: A "You got chocolate in my peanut butter" sorta sitch, maybe.

Copper and bronze weapons had one evolutionary advantage over those forged from stone: mass reproducibility. Bronze was no sharper than flint. Copper could be forged from a molten lump, for sure, but could also be poured into molds.

Bronze required some heavy lifting tho: Tin was easy-enough to extract from its ore, cassiterite. But mining these ores was nasty work "in the dark bowels of the earth." Then there was the process of mixing these molten-hot metals together, in the right proportions.

Still, our slow embrace of iron was not all that surprising, given its own requirements and limits. Iron was harder to work with, having a higher melting temperature than copper. Nor could you get a sharp edge with iron. That required steel, iron carefully seasoned with carbon. And it would still take quite a bit more time to learn that steel could be further hardened hot metal by dousing it in cold water (the opposite of what the coppersmith knew about copper, where a cold dousing softened the metal).

Perhaps the birth of the iron age could be pinpointed to the Chalybes mining tribe of Asia-Minor most likely about 1,500 B.C. A legend has it that the idea of smelting iron from the ore was birthed in these iron-ore heavy hills, a wood fire accidentally setting off the smelting process of a deposit somehow.

It wasn't until the last century B.C. did iron metallurgy hit its peak, but even then it was a craft, "the metallurgy of the smith with his hammer and his bellows." Many of the early tools for handling iron are still with us today in their basic forms: the anvil, the tongs, the frame-saws and iron file. The cast iron from furnaces would still be some time off yet.

The evolution of iron's utility followed a similar trajectory to many technologies over the years: First deployed in the decorative arts, and then quickly seized for weaponry. The Assyrians had the battering rams with a "heavy iron head." Greeks made shields of bronze, short iron swords, and 9-foot spears tipped with iron. A feudal Knight could carry as much as 100 pounds of mail or plate. The Italians were known for the best swords. Only over time, was iron deployed to build more general-purpose tools. Again, many still with us today: the hoe, the axe, the pick. Stryians (Austrians) perfected scythes. South Germans forged needles and nails from iron.

Mining declined precipitously in the third century, and little is known today of how metal working was practiced in these times. Nonetheless it continued through the fall of the Roman Empire and into the Dark Ages: “No darkness could obscure the need for tools and weapons,” Derry and Williams wrote. They also noted that he decline in metallurgical output precipitated the Roman Empire.

Metalworking skills honed in Rome migrated to France. Syrian iron workers set up shop in western Europe. The works from smiths in various Germanic tribes were imported into the Arabian areas. The Black Death (1348-50), which wiped out a third of the European population, and the concurrent Hundred Years War (1337-1453) slowed progress, as did the the exhaustion of the more easily-worked mines.

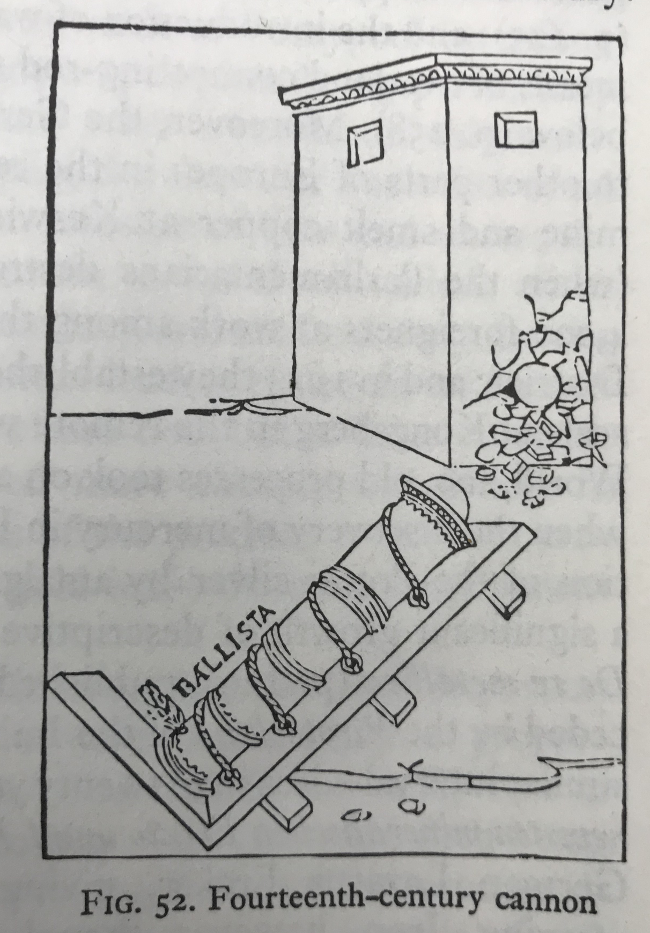

Yet this was also the time when iron became an instrumental tool of war and aggression, initially in the form of the 13th century steel cross-bow but really with the birth of the cannon by the early 14th century.

Sometime between the 13th and 15th century, the casting of iron came into being, thanks to higher furnace temperatures. "Cast iron was virtually a new commodity, which came into its own with the rise of artillery," Derry and Williams wrote. The first cannons were very small and possibly even forged from copper or brass, but the Germans with the blast-furnaces were able to cast fearsome iron cannons in a mold within a century. They marked the end of feudal lordships run from stone castles.

The industrial revolution, however, didn't kick off until iron was paired for coal.

![]()

The quality of military weapons varied in revealing ways. By the 17th century, the quality of steel

in the rank-and-file soldier’s saber/lance was“inferior to the best products of an

earlier age” when (presumably) commissioned weapons were

created more carefully, given how “faulty metal might spell disaster” for the owner.

The quality of military weapons varied in revealing ways. By the 17th century, the quality of steel

in the rank-and-file soldier’s saber/lance was“inferior to the best products of an

earlier age” when (presumably) commissioned weapons were

created more carefully, given how “faulty metal might spell disaster” for the owner.

Although rifles were in wide use at least by 1525, they weren't really put into military use until the Thirty Years War of the 17th century (where 8 million people died over a conflict of who would control the lands of the former Holy Roman Empire). Early guns for the battlefield were not exactly high-precision, which was not seen as a liability given that most soldier combat was short-range conflict anyway. The call for precision came from the sportsman hunter, in this case, and it would be another few centuries before it became agreed-upon that a spiral grooving within the barrel would produce a longer and more accurate flight for the bullet.

Actually guns were initially a bit of a hindrance in battle. Rifles required each bullet to be hammered into the bore, using a ramrod, a major inconvenience in the heat of battle. Early hand guns were even worse! They had to be fired by applying a match to torch-hole in the barrel, igniting the gunpowder. So a calvary soldier would only fire once, and rush into battle.