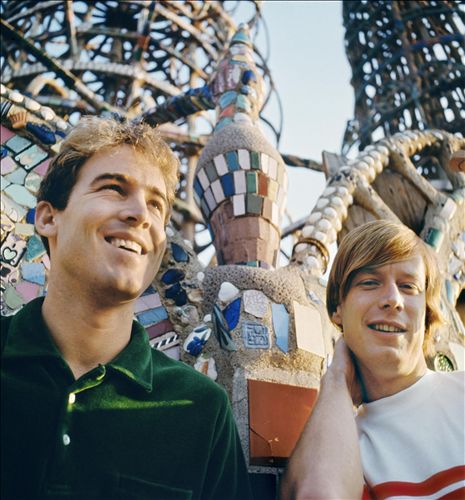

Jan Berry, the moving force behind Jan and Dean, was never an easy guy to lionize.

In a way, Jan was the opposite of Brian Wilson, the shy genius behind The Beach Boys' masterful early 60s surf rock singles. Jan was ruthlessly ambitious, brash, an outgoing high school jock, even bullying at times. He certainly enjoyed his share of white privilege, right up until he plowed his Vette into the back of a parked truck.

But before Brian saw producer Phil Spector as his main competitor, he looked up to Jan Berry, who had years of studio experience when a young Brian first met him. The Beach Boys' first regional hit single, "Surfin," is at least stylistically a rip from the Jan and Dean vocal sound, who had been up and down the pop charts for at least five years by then.

Starting as a simple surf band, The Beach Boys have become an institution of popular music, and even a part of the California mythos itself, while Jan and Dean never could quite make the transition to more serious, sophisticated pop music, despite Jan’s considerable producing chops and their use of the L.A.’s best session musicians. And the trajectory of Jan and Dean’s fame took some weirdly dark turns, before shrinking unceremoniously from public view in the late 1960s thanks to Jan’s near-deadly car accident.

Nonetheless, as biographer Joel Selvin, in his latest juicy pop music historical accounting, "Hollywood Eden," contends Jan and Dean were a set of uncannily key players in a shift of energy for early 60s teen pop music, from New York – where Don Kirshner and Brill Building writers spun out hits after hit — to Los Angeles, where indie label street hustlers like Lou Adler, Herb Albert, and Kim Fowley hastily assembled groups to record off-kilter hit single contenders picked up off the streets themselves.

![]()

A strikingly good-looking kid who played on the high school football team, Jan Berry was a rambunctious boy with a "long list of youthful indiscretions," Selvin wrote. At an amusement park, he "decked" two cops, though charges were dropped.

While on tour through the small towns of the United States, a bored Jan would sometimes revert into "Randy" a character who would slur his words and contort his face in a grotesque manner, while those around him (often Dean) would explain he was just taken out of a mental institution (This behavior would come back to haunt him badly after his car wreck in 1966). He got expelled in junior high school for stealing a rifle from the school's ROTC--Despite that he kept up good grades. Later on, he told the president of Columbia Pictures to fuck off.

Jan’s father, an electrical engineer, was a right-hand man for business magnate Howard Hughes. The family lived at 1111 Linda Flora Drive, a ranch style home with a two-car garage converted into a bedroom for Jan and his brothers, which Jan turned into a musical studio in his high school years. There, he kept a huge record collection, aided by shoplifting and by sending out letters from a fake radio station to get free copies.

He went to University High, an Olympian-sized high school at the west end of Santa Monica, serving the wealthy west L.A. neighborhoods of Bel Air and Brentwood.

Jan had met Dean Torrence – the “Dean” of Jan and Dean – in Junior High, but only really got to know him a few years later. In high school, Dean drove a 1932 White Ford pickup "that he used to ferry surfboards to the beach for weekends of volleyball and sun," Selvin wrote with characteristic aplomb.

Jan put together a singing group from his football buddies, including Dean, called "The Barrens," just to compete in a talent show. Dean sang falsetto, Jan did bass. They also pulled in eventual-Beach Boy Bruce Johnston, a wealthy kid who was classically trained pianist living in Bel Air (Interesting side note: Bruce's his father started the Rexall drug store chain).

After the talent show, the group drifted apart, except for Dean, and the duo would continue to fiddle around in Jan’s studio, recording new material.

Yet, Jan’s first hit single was not for the "Jan and Dean" duo but rather for “Jan and Arnie.” Entitled “Jennie Lee,” the song was inspired by a stripper by the same stage name, a big-breasted lady whose club admirers chanted "Bomp, Bomp, Bomp” along to her gyrations. It was this chorus that provided the song's (and Jan and Dean's) characteristic bomp vocal accompaniment.

Jan was already creating his own style as a producer. He had linked two of his father’s tape recorders in such a way to cause an echo, or reverb, emulating the sound of the doo-wop records released back east he loved. Even then, Jan was an expert in tape splicing, taking a good “bomp” from one part of the song and placing it somewhere else—all by hand.

Jan went into a studio to transfer the garage-recorded "Jennie Lee" on an acetate, just to take to parties. Dean demurred. It was the last day before he headed into the Army Reserve, and he choose instead to spend the day with his girlfriend.

So it turned out that the day Jan went into a studio to get this done, a record exec heard the song and wanted to release it as a single. He had Jan re-record song in the studio (except the vocal, which was done back at the garage for the same studio effect.

Since Dean wasn’t around for the re-recording, Jan’s other friend Arnie Ginsburg filled in. The record exec's hunch was correct: the song went on to be a top 3 nationwide hit on the Billboard charts.

Once the song was on the streets, Jan went to work marketing. He handed out to his friends rolls of dimes and lists of radio station phone numbers to call. He went into record stores and bought, stole or hid copies of the single so the shops would have to order more. Jen and Arnie toured after the record became a hit east coast tour with Link Ray and Frankie Avalon, and on another tour with Sam Cooke. They also appearing on television, including Dick Clark's "American Bandstand," to sing "Jennie Lee."

Dean first heard the "Jennie Lee" on the radio while still in the Army Reserve. He called Jan to get an explanation. As it happened, Arnie was sick of the touring life, so Jan picked back up with Dean when he returned, recording another hit single, "Baby Talk," In which Berry created a signature echo sound by recording on two Ampex recorders sequentially tied together but slightly out of sync.It was still a time in popular music when two teenagers and a tape recorder could create a hit song.

![]()

Joel Selvin is a master of biography, surfacing so many great details from the time period, without calling attention to who he is interviewing. Quotes are a rarity in this book. Instead he writes in short sharp, direct sentences. Also to his credit, the book is not entirely about Jan and Dean, but scans its attention across a number of up-and-coming singers and musicians in the L.A. era in the late 1950s/early 1960s, including Nancy Sinatra (high school mates with Jan and Dean), Sandy Denny, Phil Spector, Herb Albert, record exec Lou Adler.

Selvin points out that the California surf culture was first recognized by "Gidget: The Little Girl with Big Ideas," published in 1957 by Frederick Kohner. It’s a book about a young girl who joins a Southern California surfing gang, mostly of boys. The book proved to be immensely popular and went on to be adapted into a movie.

Both captured the emerging surf scene of southern California. Beach culture, Selvin wrote, was very similar to the Beat culture of the time. Like Beatniks, surfers ad their social attitudes, slang, rejection of convention, and alienation from mainstream society. And like any subculture, surfing culture needed its own music.

At first surf music was mostly instrumental, such as the hugely influential Dick Dale, the “King of the Surf Guitar” whose rapid staccato picking technique later formed the basis for many a hard rock and heavy metal solos.

It wasn’t until Dennis Wilson convinced brother Brian to write some songs about his favorite pastime, surfing, did songs about surfing enter the popular culture, via The Beach Boys's first regional hit "Surfin'," which came complete with Jan and Dean-like vocal hooks.

Jan and Dean first met The Beach Boys at a gig for a Valentine’s Day 1963 high school hop dance in Hermosa Beach High School. Jan and Dean didn’t have a band, they relied on backup bands provided at the show. It was easy to teach them the five or so Jan and Dean songs, and rely on the rock n roll standards for the rest of the material.

For this gig, the Beach Boys would be the backup band. They ended performing The Beach Boys’ two surfing hits at that point, "Surfin’" and "Surfin Safari" and were instantly smitten with the idea of doing more surfing music.

They had already known about the Beach Boys from the radio, KFWB specifically, where they first heard “Surfin’” with its borrowed the “bomp-bomp” background vocals.

“Jan, at age 22, was a cagey veteran, with hundreds of hours in the studio, and nearly two dozen records to his name, including two gold records,” Selvin wrote. “Brian admired Jan for his strength of purpose and take-no-shit attitude, and looked up to him.”

The week following the gig, Jan met with Brian at Lou Adler’s office on 6515 Hollywood Boulevard (Next to Dino’s Lodge). Brian played Jan a new, as-of-yet to be recorded song, "Surfin’ U.S.A."

"Immediately, Jan wanted the song for Jan and Dean," Selvin wrote. Brian told him no, that one was for the Beach Boys. Incidentally, at the meeting, Jan told Brian that he may get in trouble for copyright infringement, as the song borrowed liberally from Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little 16.” Brian said that his father, then Beach Boys Manager Murray Wilson, had reassured him that this sort of copying went on all the time, and that it would be OK (It, in fact, would not be OK. Berry rightfully sued, and eventually got a co-writing credit on the number).

Instead, Brian had another half-finished song he could offer Jan and Dean, "Surf City," with the chorus "Two girls for every boy." Jan finished the song with the help of Roger Christian, the Beach Boys’ lyric writer for their car songs (which went hand-in-hand with the popularity of the surf songs, both evoking the freedom of the California beach kids). Dean helpfully corrected a few surfing details in the lyrics. Oddly enough, he didn’t end up singing on that song; that’s actually Brian’s falsetto in there.

“Surf City” was an epic of sorts, a true culmination of a lot of talents. Glen Campbell played guitar. Legendary drummers Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer played a synchronized beat— soon to be a signature sound for Jan and Dean. A trio of Latin vocalists, the Jets, filled in background vocals.“With the promise of sex trumpeted in the record's opening moments, 'Surf City' captured a California of the mind that was instantly understood by teenagers across the land: cars, sun, sex, and surf. 'Gidget' set to a rock n’ roll beat,” Selvin wrote. In the summer of 1963, the surf song brought with it an entire surf ethos, spreading the fashion, lingo, bleach bond hairdos – in from the beach to rest of the country.

"Surf City" topped not only the U.S. Billboard pop chart (the only surf song ever to do so) but even charted as high as #3 on the R & B chart.

“Surf City” would turn out to be Jan and Dean’s most popular single, though it was the first of a two year string of near-novelty hits, including the first (and maybe still only) hit song about skateboarding, “Sidewalk Surfin’.”

Jan and Brian fed off each other. The young Brian idolized Jan’s expertise and Jan got a burst of new creative energy hanging out with Brian, rethinking how to do harmony vocals for his own music. Jan convinced Brian to ditch the other Beach Boys in the studio, and instead go with razor-sharp session musicians.

But while, in the year after “Surf City,” Brian sharpened his approach, recording for the ages, Jan Berry seemingly honed his music for teenage boys -- no doubt a big voting block of the rock n roll audience at the time. Jan and Dean songs at the time were goofy, lyrically juvenile, and generally cacophonous. Jan's songs mocked old people, nerds, and left women as bit players in his own hero narratives (all were pretty fun songs tho).

Jan, however, was no slouch when it came to arranging and producing records and, by early 1964 at any rate was more expressive in the studio than Brian. He arguably took the car song, already a staple in American pop, to its sublime form at the time, with "Dead Man's Curve" in 1964.

Cars were a huge part of the California culture. It was, after all, California was the birth place of the hot rod, Selvin pointed out. Alone among major American cities, Los Angeles had been laid out entirely after the automobile, Selvin noted. After the war, everyone could afford a car, every house had a garage. “Los Angeles and cars were made for each other.”

Christian named "Dead Man's Curve" after a stretch of Sunset Boulevard above UCLA where the road takes a 90 degree turn. Voice actor Mel Blanc wiped out on that treacherous stretch in 1961. In lush but ominous tones and eerie falsettos, the song tells of a deadly race between a Corvette Sting Ray and a Jaguar XKE. Christian once again provides a lyrical specificity, name-dropping La Brea Ave, North Crescent Heights Boulevard and Schwab's Drug Store. It painted a picture of sunny, uncomplicated California that within a few years would not be so untroubled.

![]()

Most pecular about "Dead Man's Curve" is how it accurately it foretold Jan's own nasty car accident two years later on April 12, 1966, which effectively ended the career of Jan and Dean. Driving angrily at a 80 mph down Sunset Boulevard, he had ran his Corvette into a parked lawn care truck.

The accident left him brain damaged and severely handicapped, with his entire right side paralyzed. Initially he could not speak at all. "Jan’s head was split like a coconut," the admitting nurse recalled, assuming he was dead.

Heavily tranquilized, he could only snarl and growl. Over time, he was able to speak somewhat again, but the results, especially for fans, were painful to watch. But he lost all knowledge of his former singing career -- Dick Clark actually came over to Jan's house at one point to show Jan Kinescopes of old J&D performances on American Bandstand.

There were a lot of pressures on Jan that morning of the crash. That morning, he had just found out he was called up for the draft (it must have been especially painful given he had just recorded a [painfully bad] pro-Vietnam protest song that, incidentally, Dean refused to sing on).

He was in his second year of medical school -- both him in Dean stayed in college through their singing years, realizing how precarious a career in pop stardom was then (just as it is now). So he was tired, in addition to being angry about the draft. Jan was also stinging from a breakup with his girlfriend.

And there was also the fact that Jan and Dean's career was firmly on the downslide by early 1966. A thematic album about the new television hit of the moment, Batman, had tanked. A planned movie "Easy Come Easy Go" was shelved 1965 after Jan and other crew members were severely injured in a shot involving a railroad train. The hit singles had trailed off as well. Unlike his colleagues Brian and Phil Spector, Jan could never quite get the hang of pop music's more refined, more-heavily orchestrated sound of the time.Jan had long been known for his overly-aggressive driving, speeding and pulling up on people's bumpers. And the way Selvin tells it, this was how Jan operated, always, in all aspects of his life. Moving at an accelerated rate of speed (either metaphorically or down Sunset Boulevard) does not give the driver the ability to pull away from some potentially dangerous situation, a Dead Man's Curve, if you will. Jan's way of life caught up with him in one split moment, in the form of a parked truck.