Some dirty truths about running a newspaper.

I'm sorry for the passing of the Village Voice, and for, my own kindred, the Baltimore City Paper, both of which folded last year. But I'm pretty cynical about attempts to revive them. Quarter-page ads from the local coffee shops weren't what drove those alternatively weekly newspapers, not entirely. Anybody foolhardy to start a community print newspaper might do well to find some sin money as a revenue stream.

I suspect that it was the Backpage ads that kept the Village Voice afloat through its final days. That was the underground channel to, among other things, connect sex workers with their clientèle. It was a listing more respectable daily newspapers would never take on, despite the backing of the First Amendment.

For the Baltimore City Paper, at least when I was there in the pre-Internet late 1980s and mid-1990s, a healthy source of revenue came from ads for 1-900 phone chat ads, where the Johns would call a number to have a sexy chat with a lady. Pay-per-minute sex-talk was big pre-Internet. In the 1990s, a phat era for such alt weeklies, some issues would have 100 pages a week or more, buoyed by a goodly portion of phone sex ads in the rear. Lusty Come-Hither Full! Page! Ads! And Lots!

What I heard, anyway, from the back halls of the City Paper offices, was that the paper ran those ads for free! It just took a cut of the profits that came from them. Whatever the truth, there was a lot of money coming in from those Full! Page! Ads! Print was/is not inexpensive.

Of course, backlash about them arose from time to time, from writers, editors and high-minded readers who felt the editorial integrity was being sullied by the exploitative nature of these adverts. But this issue was always a non-starter. Like steroids (or, heh, Viagra), sin money pumped up the editorial pages. Any paper, to be successful, had to maintain a 40/60 split between ads and actual content, more or less. Something had to hold the ads apart, as the art department used to crack. More ads, more reporting.

I liked calling this business model the "Liquor in the Front, Poker in the Rear" approach. Apologies for the horribly sexist name. But the concept holds: Everyone enjoys liquor, but the real money is with the poker game in the back, even though it is probably illegal, or at least offensive to some faction of the community. Hence the premium people are willing to pay. It's the serious sin money in the back (of the book) that pays the rent for the joint. Get yourself some of that.

Playboy also operated on a variation of this model, at least from a journalistic point of view: It could afford to hire the best writers, and do some of the best long-form reporting, because of the seeming never endless supply of men who bought up the magazines for the sexy pictures. This approach has its adherents even in the digital age: Facebook didn't exactly turn down the ad money for the 2016 Russian election meddling, however fervent the subsequent protestations of ignorance from the social media giant's execs.

Baltimore is a big newspaper town, ex-Baltimore Sun reporter David Simon once said, in one airline magazine or another. When I first read that I thought he was being a bit daff. By the time I started working at the City Paper in the late 1980s, there was only one daily newspaper left, the Sun. The competing News American had just gone out of business. I remember walking through the basement of the recently-vacated News American building on Lombard Street with the gigantic printing presses, beasts of an earlier era, sitting ghostly silent. I was there with my City Paper boss Christine to scavenge some used office furniture.

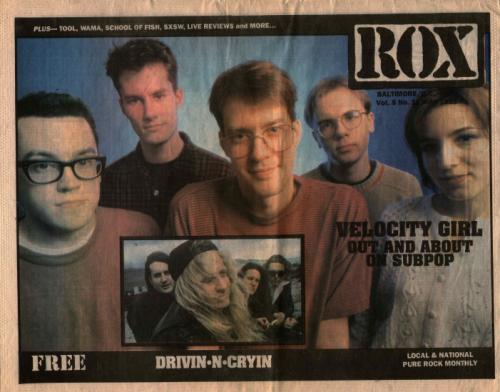

Simon was right though, the city had a lot of smaller newspapers and magazines, many of which you could pick up, for free, at the supermarket or bar. Many of these I scribbled when I decreed myself a writer. They didn't pay much, if at all. The city had not one but two monthly magazines for local music, the ever-diligent Maryland Musician and its evil offshoot ROX (which I wrote for in exchange for weed and free review CDs). I also wrote for an upstart arts publication, Art In Progress, and the shortly revitalized Harry, Baltimore's first hippie underground paper, started in the early 1970s that was revived for a spell in the early 1990s by the indefatigable Tom D'Antoni to rival the City Paper.

I distinctly remember the last all-hands meeting for Harry, which had brought in a consultant to address the paper's financial woes. Readers loved Harry. And for a few months in 1991, each monthly issue ran head-to-head with the City Paper in terms of entertainment-per-page. The reason why there was no money, the consultant explained, was simple: not enough ads. After generous seed funding from some secret benefactors, the paper's coffers quickly ran dry. It had no phone sex ads. Hippie health food stores and arty high-end nick-knack shops run by the bored Hunt Valley housewives would buy small, inexpensive, quarter-page ads, but there just weren't enough them -- or enough salespeople to hunt them all down -- to come anywhere close to that 40/60 split. At least the local music magazines got full page ads from the record companies and music stores, their own version of dirty money (from "The Man") I guess you could say.

After about six spirited issues (where I got to write about tattoo parlors, the underground music scene and other clandestine subcultures of the city), Harry had just enough money in the coffer for one more issue. I remember the distinctive divide in the all-hands meeting, with the writers and artists vehemently arguing that one last issue should be printed. "We'll figure something out," the creative types kept repeating, and the consultant facing down the whole room asked what that something would be, exactly. Many volunteers wanted to write for the paper, but no one wanted to volunteer to go out and sell ads. No answer was formulated though, and the paper folded.

And this was in 1991, a good decade before the Internet would do serious harm to the print periodical industry. Many of them ran aground in the years since because they ran out of money. Print is a tough business. Businesses who buy ads expect a 90-day period to pay the newspaper for the ads they run, yet the printer wants to money right away. The newspaper must have the cash to provide that float in the middle.

Another merit to the sex ads was that, however controversial, they were a reliable source of income as well. Nothing is more reliable than people's proclivity towards self-pleasure.

I need to stipulate that I have no actual first-hand experience with the business side of City Paper. Everything I know is what I've overheard in the hallways and happy hours. But something I do have a great deal of knowledge about, however, was City Paper's actual circulation, or where in Charm City those papers were actually ended up. There was a bit of peculiar accounting there too, I could probably confess now.

I started writing for the City Paper in 1994 or so, though for years prior to that I worked in the circulation department, as a part time job to help me through college. Each Wednesday at about 6 AM, a tractor trailer filled with 90,000 copies of that week's City Paper would arrive at the loading dock. It was the job at the circulation department - which was basically my boss Christine and myself - to get them out to about 1,500 locations across the city, preferably by noon that day.

Most of the actual delivery was done by a set of 15 drivers, various gypsies and societal outsiders with ragged trucks and vans, who would show up every Wednesday to load up the papers and distribute them to the newspaper boxes, pizza joints, grocery stores and bars. They god paid $0.01 per paper, and if you hustled you could make $300 for a day's worth of toting bundles to their final destination (I've since owned vehicles, such as a truck, that can hold a lot of newspapers, in case all goes south).

One of my particular duties was to spread out the delivery of papers evenly in such a way that at least 95 percent - preferably 98 percent - would be gone by the following week, which is what we'd call a "return rate" of 2 to 5 percent. This wasn't too hard to do, given everybody liked reading the City Paper, or at least picking it up to hate on it. It was free, and, again, before the Internet occupied everyone's spare moments. So part of my job was to check the return rates, and adjust the number of papers each location got so that there were just enough so that there would not be any leftovers.

The tricky part was getting them in the right zip codes. In a precursor to today's ultra-targeted digital ads, the City Paper would sell ads based on the demographic of the city. Naturally, advertisers wanted to get their notices in front of those people with the most money. And one reliable determiner of who had the coin were zip codes for the (comparatively) wealthier neighborhoods of the city - Towson (21204), Roland Park (21210), Pikesville (21208), Federal Hill (21230), and so on. So part of my directive was to funnel as many papers as possible to these, ummm, more desirable neighborhoods.

And, not surprising demographically, these neighborhoods were, for the most part, where white people lived. Baltimore was then, as anyone who watched The Wire knows, a racially divided city. Neighborhoods with mostly black folk dominated the west side of the city - everything west from Martin Luther King Boulevard (yes, that truism held in Baltimore) out to the Beltway - and in pockets of the east side, roughly north of Eastern Avenue.

None of those neighborhoods - those "less-desirable" zips - got newspapers from us. You could not find a City Paper box in the entire west side of town, not in Harlem Park, Lexington Terrace, Edmondson, or Winchester. In short, City Paper was a newspaper accessible mostly for white folks (though, to be fair, it was a demographic thing, not a racial one per se. There were many poor white neighborhoods CP didn't serve either, such as Brooklyn or Essex). Occasionally someone would notice there would be no City Paper boxes at, say Mondawmin Mall, but since white folks in Baltimore tended to stay clear of places like Mondawmin Mall, they were completely oblivious to this fact.

This segregation was not, to be clear, an editorial decision. Editorially, the City Paper strived to cover the issues in these areas, many of which were feeling the brunt of extreme impoverishment. But black folks for the most part never saw these articles because they never saw the papers, and, in the end, were much better served by the two that did serve this constituency - The Baltimore Times and the Afro- American.

The big exception here, if only by my own fiat, was the Santoni's supermarket on 3800 East Lombard Street downtown. The west side was also underserved by decent supermarkets, and one of the few viable ones on the side was the Santoni's. Fortunately for my distribution spreadsheet, it under a desirable zip code (21224) that was also desirable for the downtown office workers. So the City Paper kept a few stands there, right in the front of the store.

The hunger for newspapers at Santoni's was voracious. Pretty much endless. You can only shift so many papers in a Catonsville pizza joint, so usually I had a few hundred or even a few thousand extra to distribute on any given week. But I knew I could deliver them to Santoni's and they'd be gone within a few days - and not just because someone was having a crab feast (crab houses being another reliable place to gift with excess papers for reasons obvious to anyone who indulged in this Old Bay-seasoned dining tradition). On certain weeks, we'd deliver as many as 3,000 papers to Santoni's - 3 percent of the total circulation. And the store manager often asked for more - he saw the customers loved the rag.

The advertisers may not have liked it if they found out their ads were being seen by folks who probably couldn't afford what they offered, but fuck 'em, people wanted to read the City Paper, and it was my job to deliver the word to the people.

As the most junior circulation assistant, it became obvious pretty early on to me that City Paper could probably double the number of papers circulated each week by simply expanding into the west side. But the Powers-That-Be never took me up on the idea. The print run was expensive enough as it was and increasing the circulation to this area would only dilute the demographic.

The City Paper, "Baltimore's Free Weekly," operated under this slight-of-hand, for the years I was there, and perhaps even the decades after. Did this restriction to the demographically desirable help the CP get by at the time? Maybe. But maybe this enforced diet was what starved the newspaper in the long run, making it prey for the larger Baltimore Sun.