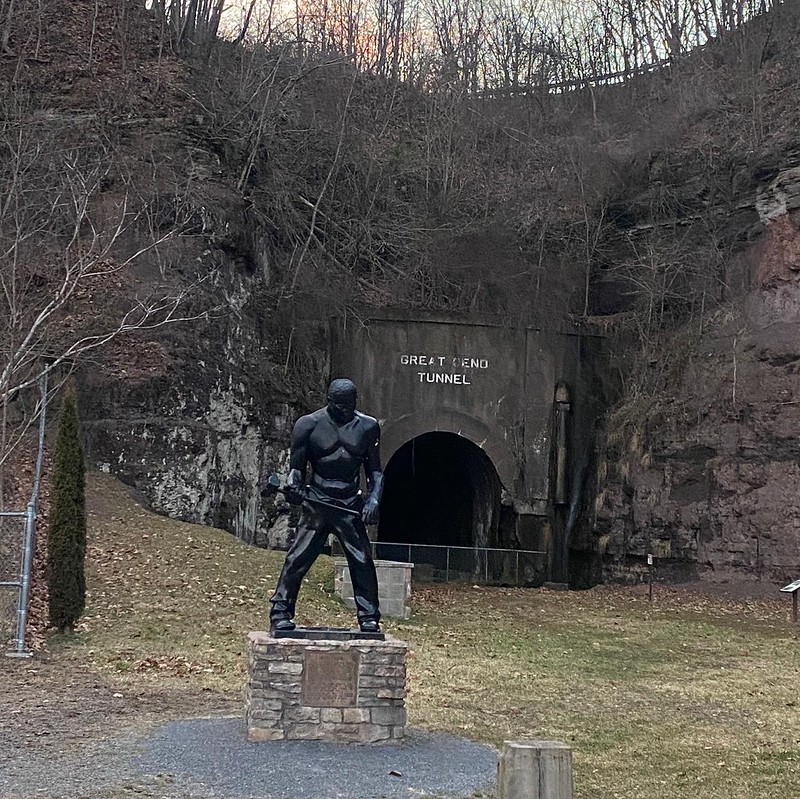

The train leaves the Talcott WV station and rolls into Big Bend tunnel, a hole carved into the rock-solid Appalachian mountain, and the engineer blows a whistle for old John Henry. Poor John Henry. He gave his life so the rest of us could go a bit further on up the road.

“His was the triumph of the human spirit,” wrote Colson Whitehead in his 2001 novel John Henry Days.

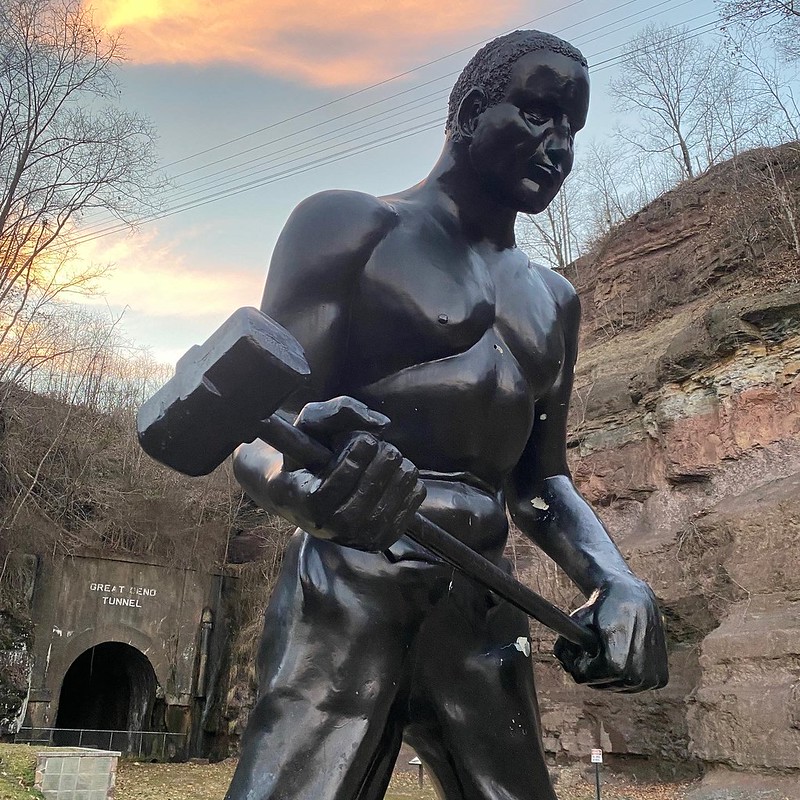

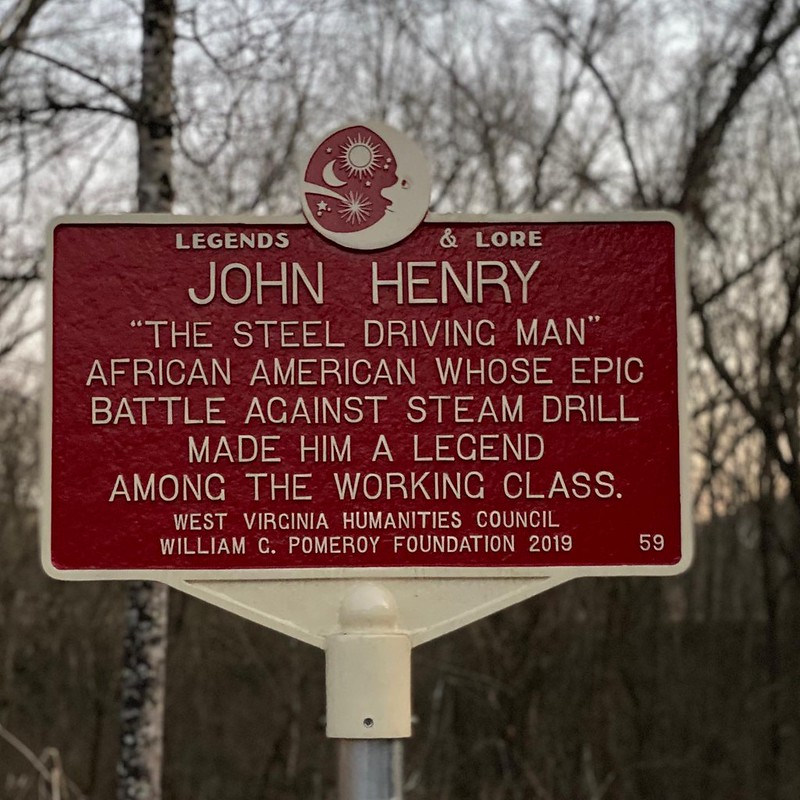

Today, there is a 750-pound bronze statue of the man at John Henry Memorial Park, John Henry Park, Talcott, WV.

His is the ultimate tale of man-against-machine, holding both the triumph and defeat. The man wins, but even though he is the mightiest of men, he still dies. The machine, slower than the man, will nonetheless just keep chugging away. The descendants of that steam drill will finish the tunnel, then finish a much larger tunnel, rendering the one that killed John Henry obsolete.

The legend of John Henry has been passed down now for centuries. But why does his story resonate? And did he ever exist?The deeper you dive, the murkier it gets.

But John Henry is also the story of a freed black slave, who toiled for white millionaire bosses to enjoy even the meager lifestyle of the workcamp, a shantytown lean-to with floorboards separated to allow the cool air to come up into room in the summer time. He worked for pennies and outgunned his white peers.

Those who dare enter the tunnel will hear his hammer singing in the darkness. “This is the deathlessness of the human spirit,” Whitehead wrote.

It took Chesapeake and Ohio three years to complete the tunnel. The railroad could have gone around the mountain, but that would add to the travel time between Virginia and Cincinnati. The railroad companies, interested only in profit, were nonetheless weaving the country's isolated towns in the fabric of the nation.

Much of the mountain they were digging through was solid rock. Dynamite provided the best way to break the rockbed into chunks that could be carried out. The explosive needed to be embedded into the rock though, hence the need for the steel driver.

So men like Henry were hired to drive spikes into the rock. They worked in teams. One guy would hold a bit and the other guy would hammer it into the rock, making enough space for a stick of dynamite. They used 10-pound or 20-pound sledge hammers, rubbed with brown oil to the keep the wood limber, absorb the shock. As the men worked, they would sing songs to keep rhythm of their strokes.

The legend goes that the C&O were testing a mechanical steam drill, one the manufacturer said

would do the work of multiple men. "God created the mountains but man created the steam drill," Whitehead wrote.

The legend goes that the C&O were testing a mechanical steam drill, one the manufacturer said

would do the work of multiple men. "God created the mountains but man created the steam drill," Whitehead wrote.

Eyeing the big unwieldy prototype, Henry said he could easily beat such a machine. A recent mine collapse had killed five workers, Henry knew that a contest, which could be bet against, would enliven morale.

The contest was not as one-sided as it might appear. A machine was more cost-effective to be sure, able in theory to drill for $0.05-an-inch

vs $0.11-an inch for human labor. But they were unreliable. Their bits got mucked up with the shale dust, the drill bits would often break.

So it is feasible that John Henry could have won.

The contest was not as one-sided as it might appear. A machine was more cost-effective to be sure, able in theory to drill for $0.05-an-inch

vs $0.11-an inch for human labor. But they were unreliable. Their bits got mucked up with the shale dust, the drill bits would often break.

So it is feasible that John Henry could have won.

And John Henry did win, the story goes, drilling a total 14 feet into the rock, while the steam drill only did 9.

But then, the legend goes, he died that very day.

Scholars never agreed if this contest ever happened, or even if John Henry actually existed at all. The C&O kept scant records of the workers

(and good luck searching centure-old documents against a name as generic as John Henry).

Nor was there any paperwork about testing a drill.

Scholars never agreed if this contest ever happened, or even if John Henry actually existed at all. The C&O kept scant records of the workers

(and good luck searching centure-old documents against a name as generic as John Henry).

Nor was there any paperwork about testing a drill.

Within a year of each other, two folklorists interviewed an overlapping set of people who said they knew John Henry or claimed to have witnessed the contest. All roads led nowhere. The white scholar concluded that the event happened, while the black scholar came to the opposite view, that it never happened.

The deeper the scholars dug into John Henry, the less of certainty they knew.

The deeper the scholars dug into John Henry, the less of certainty they knew.

The sculptor did not know what John Henry looked like so he conjured "what the story worked on his brain" and reconstructed what such a man would look like.

The legend itself is a reality, a fact in its own right. Like the statue itself, or the tunnel

"was unremarkable in its surface effects, and yet it had generated out of its rich oil such an abundant crop of lure."

The legend itself is a reality, a fact in its own right. Like the statue itself, or the tunnel

"was unremarkable in its surface effects, and yet it had generated out of its rich oil such an abundant crop of lure."

For laborers, John Henry became a shorthand for super strength and super endurance, and in some cases maybe even sexual prowess.

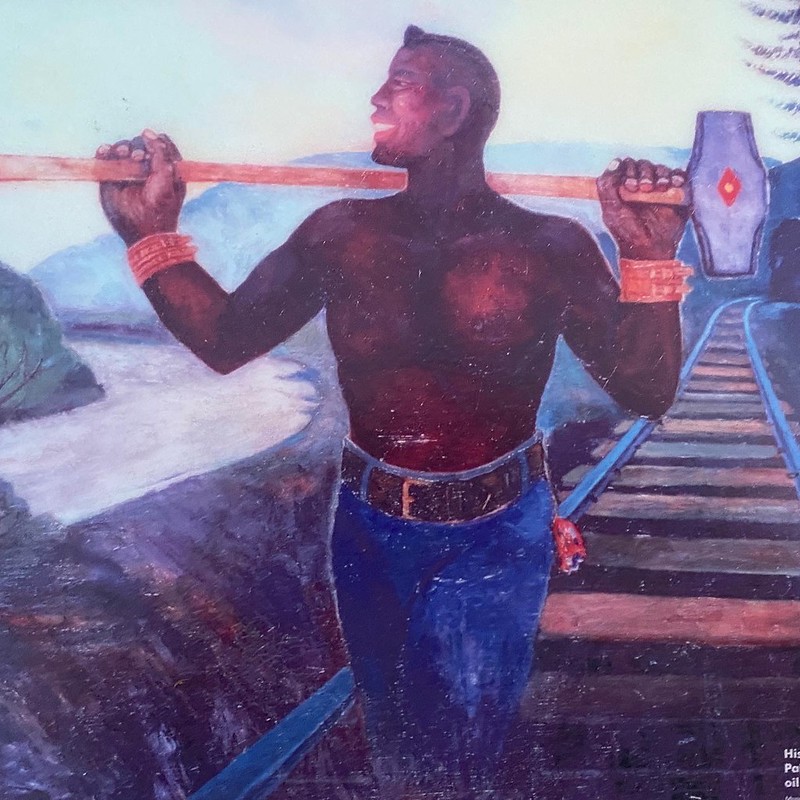

A worksong, the kind black men sang to keep the rhythm of laying track, came together around the legend of John Henry.

It quickly moved and evolved across construction camps, wharfs and saloons across the country. Today, there are at least

over 120 recorded, and widely-varying versions of the song.

A worksong, the kind black men sang to keep the rhythm of laying track, came together around the legend of John Henry.

It quickly moved and evolved across construction camps, wharfs and saloons across the country. Today, there are at least

over 120 recorded, and widely-varying versions of the song.

As a slave, the young John Henry carried water in the mines, and so he knew of the cool climes of the mountains, Whitehead observed. And this is why he signed up for the railroad work, easy money for his family back home. But when he arrived in Talcott, and saw this mountain, he knew that this would be the one to kill him.

"I'm going to die with a hammer in my hand, Lord, Lord"

In Whitehead's novel, a heated couple sneak into the abandoned tunnel to make love. She hears a

hammering far off, and is spooked. "But what about John Henry, " she asks her lover.

I'll give you John Henry, he responds, putting her hand on his crotch.

In Whitehead's novel, a heated couple sneak into the abandoned tunnel to make love. She hears a

hammering far off, and is spooked. "But what about John Henry, " she asks her lover.

I'll give you John Henry, he responds, putting her hand on his crotch.